Resilience and autonomy are two of the major reasons communities undertake microgrid projects. Resilience is becoming more important due to climate change, extreme weather events, cyber-attacks, and grid vulnerabilities, which can lead to prolonged utility outages. Community resilience microgrids are an effective means of ensuring energy supplies even when the utility grid goes down. They also give the community more control over the source and sustainability of their energy, and can improve power quality and reliability and reduce cost volatility. Thus, a first step in the microgrid development process is to examine and determine what the community’s priority goals are.

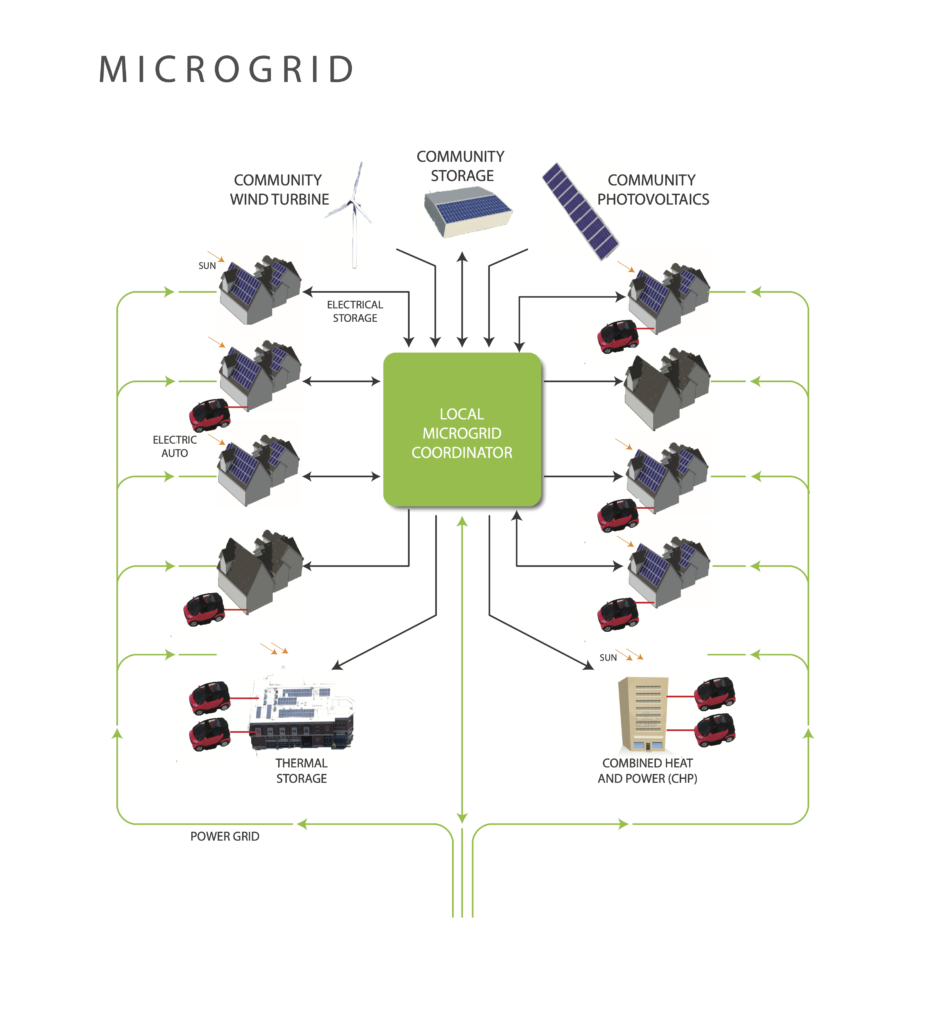

Technically, a microgrid is a group of interconnected loads and distributed energy resources within clearly defined electrical boundaries that acts as a single controllable entity with respect to the grid. In other words, it includes on-site generation (such as solar PV), the devices using electricity (loads), the distribution network of wires to connect them, frequently a battery energy storage capacity, and communications and controls to make all this work optimally and in support of the community’s goals (for example, least cost, most sustainable).

When a utility grid is available, a microgrid can connect and disconnect to enable it to operate in both grid-connected or “island” (disconnected) mode. This leads to more favorable economics when in connected mode through exchanges of energy and value with the utility grid; and to community resilience and enhanced energy sovereignty when in island mode, as “critical” and “priority” uses of energy can be continuously supported for extended periods. (Note that grid-connected solar arrays, unless they include a transfer switch or “smart inverter” — which some utilities still don’t allow — are automatically shut down during a utility outage for safety reasons, and won’t supply electricity until the utility service is restored.)

Tribal commercial and community buildings and operations can increase the value of resilience and the financial feasibility of a microgrid, especially for gaming tribes if casinos can maintain operations, or are used as emergency facilities.

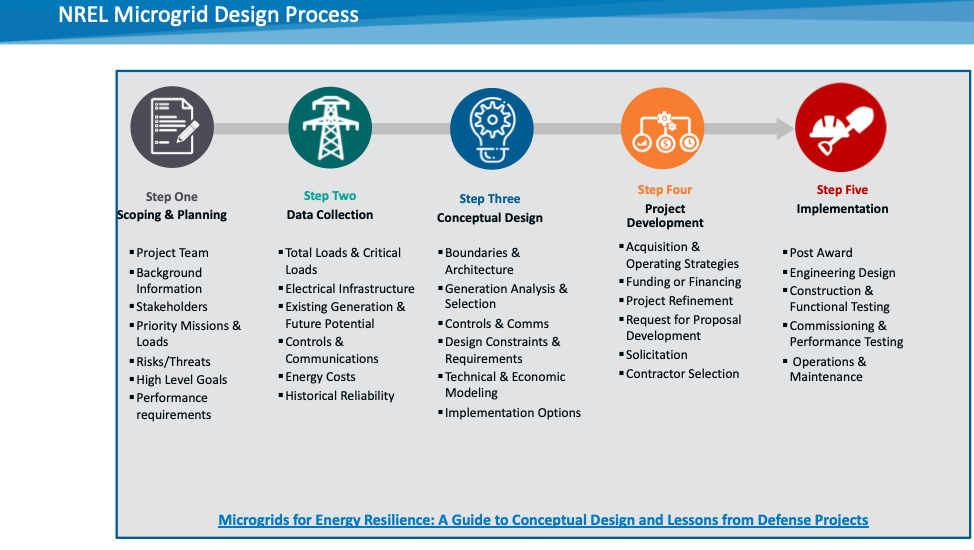

Implementation Pathway

Two illustrations of microgrid planning and development processes appear below. The first is from the National Renewable Energy Laboratory’s “Microgrids for Energy Resilience: A Guide to Conceptual Design and Lessons from Defense Projects,” and provides insights into technical and data requirements and sequences:

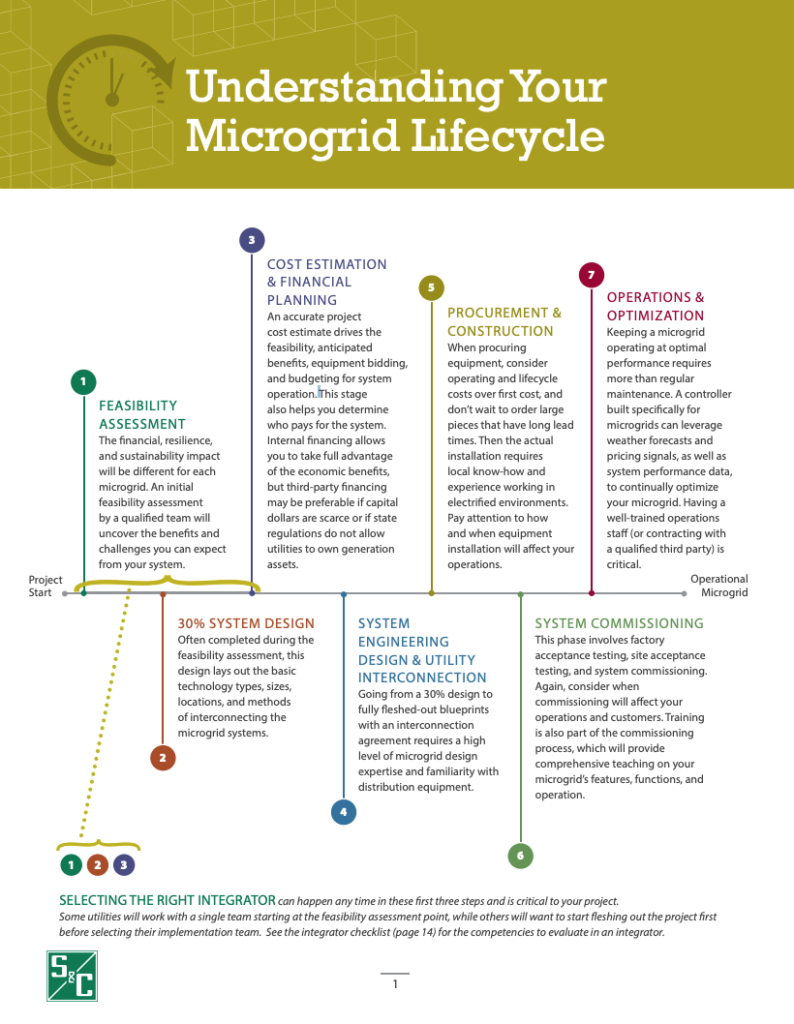

The second graphic is reproduced from S&C Electric’s “How to Build a Microgrid” publication, and shows the main steps involved in developing a project (S&C Electric is a leading microgrid integrator, which is generally a necessary part of the team and an early step in development; others integrators include Siemens, Schneider Electric, Ameresco, and Hitachi/ABB):

Examples

Rincon Band of Luiseno Indians Solar Microgrids Project “will assure resilient and sustainable energy supplies for several facilities and services essential to the health, safety, and welfare of the Rincon Band, while reducing lifetime costs of energy and outages, and creating infrastructure and systems to support tribal sovereignty and self-sufficiency.” The systems are expected to save nearly $500,000 annually, and more than $9.2 million over 25 years.

Blue Lake Rancheria Tribe Microgrids: The Blue Lake Rancheria community microgrids project has attracted national attention and recognition for its achievements in sustainability and resilience, as well as economic performance. It provides approximately $150,000 in annual electricity savings, and was funded by a $5 million grant from the California Energy Commission through their EPIC program. It is featured in the DOE Office of Indian Energy’s 2019 Tribal Energy Webinar Series: “Tribal Microgrids, Energy Storage, and Resilience,” and this DOE Blue Lake Rancheria and Citizen Potawatomi microgrids webinar.

San Pasqual Band of Indians Microgrid Project: “Tribal Benefits (Preliminary): Strengthening the tribal administration’s ability to provide critical public services including first response (both fire and police), reservation security, emergency sheltering and evacuation capacity, and administration command and control capabilities. Saving approximately $45,190 in electric energy costs per year on average, or $1.13 million over the system’s 25-year useful life. Reducing net electric energy imports to the reservation by approximately 278,481 kWh per year. Producing approximately 6.5 GWh of renewable electricity over the system’s lifetime to offset about 96% of the tribe’s grid electricity consumption for the five facilities served.” The total project budget was approximately $1.6 million, funded 50% by a DOE grant with an equal cost share from a GRID Alternatives grant, and tribal in-kind and cash contributions.

Soboba Band of Luiseno Indians Microgrid Project: A solar plus storage microgrid will provide resilient power for the Soboba Band of Luiseño Indian lands, an area threatened by wildfire-related power outages in California. The California Public Utilities Commission calls the tribe’s lands a “Tier 3 – extreme threat” area that suffered multiple wildfires over the last two years. The microgrid will provide 50 kW of solar generation with a 0.5 MWh battery backup to the fire station site. The location is also the tribe’s incident command center, emergency shelter and distribution point for the tribe’s food, equipment, and supplies.